Part of the proud history of the United States Marines Corps is its heraldry and uniforms. The insignia, emblems, and uniform of the U.S. Marines are some of the most recognizable images in the country. The following essay provides a general overview of the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor and the various forms it has taken over the last two hundred years. The Eagle, Globe, and Anchor—the most distinct of all Marine Corps marks—has a long and storied heritage as the emblem for the Marine Corps. It is the basis for the flag, the seal, the branch-of-service insignia, and many of the logos.

Marine Corps Branch of Service Insignia

Distinct from the Marine Corps Emblem is the Marine Corps branch of service insignia. The branch of service insignia is based on the Marine Corps Emblem, but it does not include the “SEMPER FIDELIS” scroll in the eagle’s beak—an eagle on top of a globe showing the Western Hemisphere, in front of a fouled anchor. There are two types of Marine Corps branch of service insignia: the officer’s insignia and the enlisted insignia. The officer’s insignia is made of gold- and silver-colored metal for dress insignia and is non-glossy black for service insignia—with the proportions of the insignia elements dependent on the size of the globe, which is determined by whether or not it is used on the collar, dress cap, or service cap. The enlisted insignia is made of gold-colored metal for dress and is non-glossy black for service insignia.

On left: Current officer service insignia / On right: Current enlisted service insignia

Eagle-eyed observers will also note that the officer and enlisted insignia have different levels of geographic detail. For example, enlisted insignia include the island of Cuba, while the officer insignia does not. While there are many stories for why this is so—ranging from the composition of forces during the Spanish-American War to the Bay of Pigs—practical concerns generally dictated this difference. Whereas the enlisted insignia is stamped from a single piece of metal, the officer insignia is composed of several pieces of metal and mounting a separate piece to show Cuba was found to be too difficult or not aesthetically pleasing. There has also been a long tradition of differentiation between officer and enlisted insignia in the United States Marine Corps. It was standard practice for individual officers to purchase their own insignia, with it not being uncommon for fine jewelers (ex. Bailey, Banks & Biddle) to manufacture insignia for United States Marines. Regulations dating back into the early 20th and 19th centuries also left much—including the exact design, shape, and standards of the hemisphere’s geography—to the stylistic interpretation of the individual manufacturers or jewelers hired. With insignia coming from numerous sources, this created a wide variety in the level of detail used and a distinct lack of uniformity. Furthermore, enlisted emblems had standard samples that were available from Marine headquarters to aid manufacturers. It was not until after the adoption of the current official seal and emblem in the 1950s that these differences and variations were codified into their now-standard forms.

Marine Corps Seal

The Marine Corps Seal consists of a bronze Marine Corps Emblem, displayed on a scarlet background. The scarlet background is encircled by a navy blue band, inscribed with “Department of the Navy, United States Marine Corps” in gold letters, and edged in a gold rope rim.

The Marine Corps Seal was based on a revised version of the Marine Corps Emblem, which substituted an American bald eagle for the previously-used crested eagle. On June 22, 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed an executive order that approved the use of the design, which had been requested by the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr.

Unlike the Marine Corps Emblem (the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor), the Marine Corps Seal is reserved FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY.

Marine Corps Emblem – The Eagle, Globe, and Anchor

In its over 200 years of existence, the Marine Corps has used several different emblems and official insignia, yet no design has had greater staying power than the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor (EGA). Eagles and anchors have been used in Marine Corps insignia since the turn of the nineteenth century.

1804 -- For example, in 1804, the buttons of Marine uniforms displayed a fouled anchor with an eagle perched atop it and surrounded by thirteen six-pointed stars. At a later point, the stars were changed to the current five-pointed version, though the original form can still be seen in the logo of numerous organizations, including the Marine Corps History Division.

USMC Uniform Button, c. 1806-1850s (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps)

This device, an eagle and fouled anchor with thirteen stars, represents the oldest military insignia in continuous use in the United States.

1812 -- Another milestone in the development of Marine Corps insignia worth noting is the enlisted Marine cap insignia for the early nineteenth century, particularly the period encompassing the War of 1812. This device, which would have been made of brass and displayed on the front of a black shako cap, was similar to devices used by the Army during this period.

Image of “Cap Plate, Enlisted 1804-1812 (Reproduction)” (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps)

The Marine Corps version featured an eagle grasping a ribbon in its beak, with the word “FORTITUDINE” (meaning “with courage”) emblazoned on the ribbon. An eagle with outstretched wings was perched on a fouled anchor, surrounded by various implements of war: flags, drums, a mortar, cannon balls, and cannon. At the bottom of the emblem, one found the word “MARINES”.

1850s – 1890s -- A variety of emblems would be used in the early nineteenth century: laurels and wreaths emblazoned with the letters “U.S.M.”, along with other styles of eagles, anchors, and wreaths. By the time of the United States Civil War (1861-1865), the Marine Corps insignia had evolved into a light infantry horn and a letter “M” inside of the horn ring. In formal settings, the horn was placed on a field of stars and stripes and surrounded by laurel.

(Figure 3. Officer’s Full-Dress Cap Ornament, 1859-1876[?]) (EGA, p. 3)

USMC Full Dress Insignia, c. 1860s. (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps)

After the U.S. Civil War, it was decided by the 7th Commandant of the Marine Corps, Brigadier General Jacob Zeilin (1806-1880), that the Marines needed a more distinctive—more unique—insignia than the horn and “M”. The horn and “M” was similar to the insignia used by other organizations, such as units of the U.S. Army. With this new design, Commandant Zeilin drew upon the history of the Marine Corps and the influential legacy of the British Royal Marines: “…a Corps of over two hundred years eminently distinguished for its service on land as well as for its legitimate duty with the Navy.” (Decorations and Medals, 11) The emblem created included: a crested eagle, a view of the Western hemisphere, and a fouled anchor. Drawing on the tradition of the British Royal Marines and the United States Marine Corps of serving on land and sea (“Per Mare, Per Terram”), the emblem is rich in symbolism. The eagle and the globe represented the global reach and projection of the power represented by the Marine Corps. The fouled anchor displayed the naval tradition of the Marine Corps and the ships on which it served.

[ON THE LEFT -- “Figure 16. – Enlisted undress cap ornament 1876-1892; enlisted fatigue cap ornament, 1876-1881 as illustrated in the 1875 Uniform Regulations”] [EGA, p. 15]

ON THE RIGHT -- “Figure 25. – Enlisted black helmet Corps device, 1892-1904. Type (1) consisting of a slightly different pattern from Type (2) and containing on the back of the device a screw post fitted with a milled nut for securing it to the helmet.” [EGA, p. 24]

LEFT: USMC Black Helmet Enlisted Insignia, c. 1892-1904. RIGHT: USMC Eagle, Globe, and Anchor Epaulette, c. 1868. Photos courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Though this design bears resemblance to the modern EGA, there are several differences worth noting. First, the eagle was a crested eagle, which is not specific to the United States, rather than the American bald eagle. Until the 1920s and 1930s, there was also wide variation in the exact shape of the eagle and the angle of its wings. The globe showed the Western hemisphere, but over the years there was wide variation in the shape and detail shown of the continents. The fouled anchor line was also not always uniform—with some examples wrapped several times around each fluke and others wrapped once around the shank and crown. While the Marine Corps changed many of the details for the EGA in the twentieth century, 1868 saw the first official adoption of the EGA as the Marine Corps emblem: being used as a cap ornament. However, to give units time to procure new insignia and emblems from manufacturers, its use was delayed until after July 1869. The horn and “M” was also still used for officer’s epaulettes until November 1869. In May 1875, new Uniform Regulations were issued (to be effective 1 July 1876) and codified the use of the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor as “the sole emblem of the United States Marine Corps.”

1925 -- On May 28, 1925, a new, standard version of the EGA was approved by the Commandant of the Marine Corps Major General John A. Lejeune and the Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore D. Robinson. This version, designed by Staff Sergeant Joseph H. Burnett, featured: a side-looking eagle grasping the middle of a “SEMPER FIDELIS” banner on top of a globe, featuring the detailed view of the Western hemisphere with curved lines of latitude and longitude.

[Illustration of 1925 EGA, from EGA]

USMC Eagle, Globe, and Anchor Collar Insignia, “Droop Wing”, c. 1920s. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

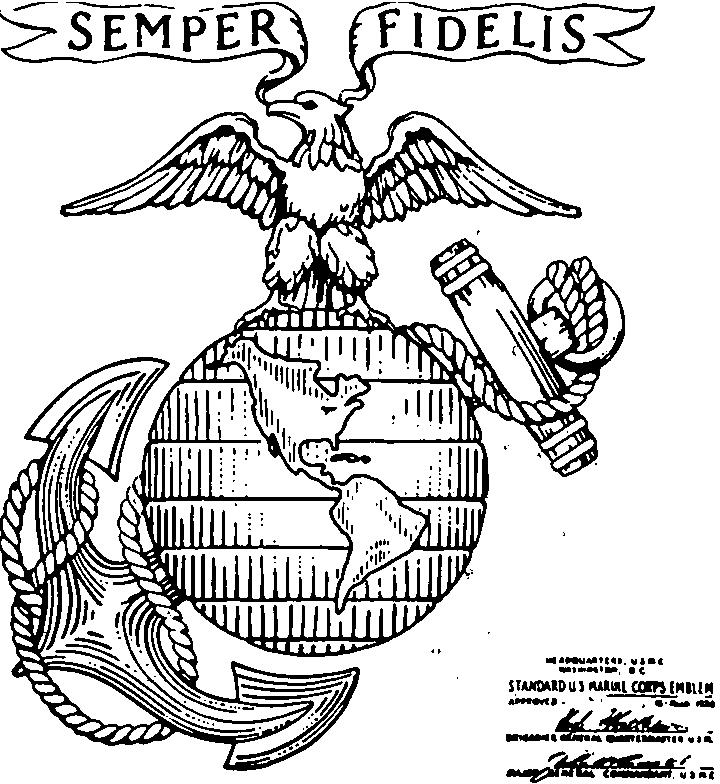

1936 -- The Marine Corps further developed the 1925-version of the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor on March 16, 1936, when a new “STANDARD U.S. MARINE CORPS EMBLEM” was approved by the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Major General John H. Russell, and the Secretary of the Navy, Claude A. Swanson. The 1936 version altered the stance of the eagle, regarding both its wings and head, and used straight lines of latitude. This new version was not readily available to Marines, as factories needed time to re-tool and the Marine Corps did not provide a standard pattern for manufacturers. This led to a large amount of variation in insignia design during this period—a fact that would be amplified during World War II, when material shortages and supply chain changes forced units to think outside of the box. For example, the First Marine Division, operating out of Australia in 1943, was forced by supply shortages to procure uniforms and their insignia locally.

[Illustration of 1936 EGA design, from EGA]

Australian KG Luke Eagle, Globe, and Anchor, c. World War II. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

1954 – 1955 -- These years saw the final major changes to the Marine Corps emblem from its earlier forms to its current form. On June 22, 1954, Executive Order 10538 (“Establishing a Seal for the United States Marine Corps”) was signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. This order established the current Marine Corps seal, which features: the Marine Corps emblem on a scarlet background, encircled by a navy blue band, inscribed with “Department of the Navy, United States Marine Corps” in gold letters, and edged in a gold rope rim.

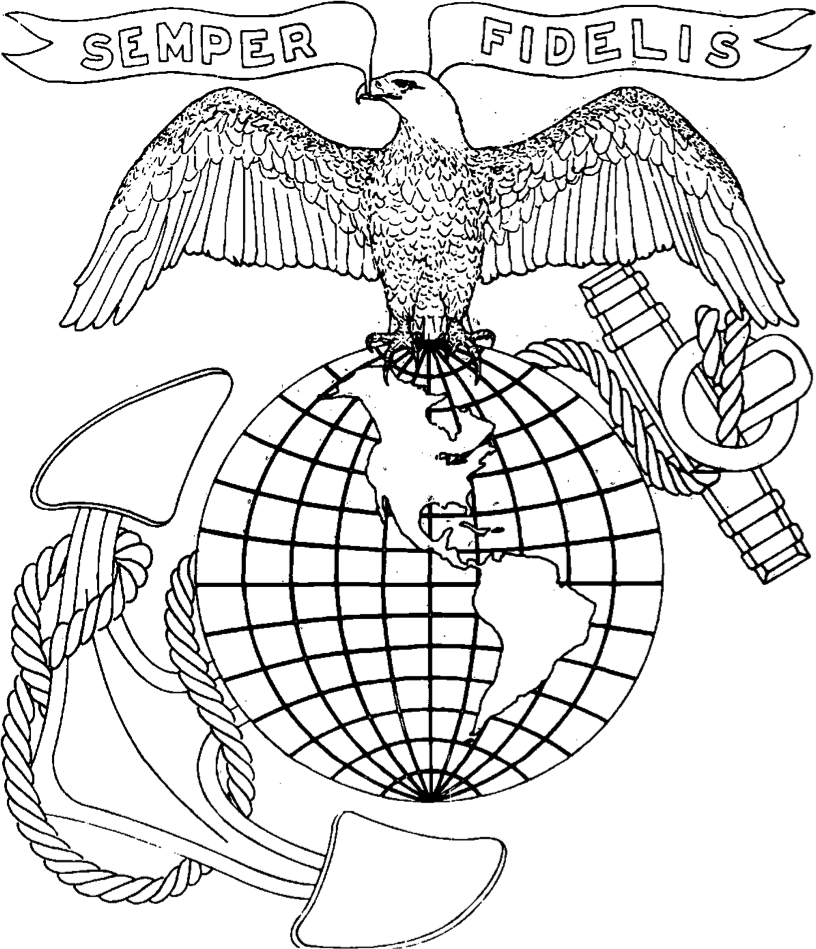

The Current Emblem of the United States Marine Corps

The Marine Corps adopted the current Eagle, Globe, and Anchor (EGA) as its emblem concurrently with the Marine Corps seal. In contrast with earlier versions, it featured an American bald eagle, with the eagle’s beak grasping the beginning (rather than the middle) of the “SEMPER FIDELIS” banner.

The Marine Corps also maintains an official recruiting version of the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor.

To this day, the EGA is one of the most widely-recognized symbols in the world, having been used in one form or another over a century. While the details of its form have changed, the major elements—eagle, globe, and anchor—have not, making the EGA a “symbol of the remarkable esprit of the U.S. Marine Corps.” The Eagle, Globe, and Anchor “has survived…with honor and acclaim and consequently it has been chosen as the basis for the emblem of amphibious forces of nations throughout the free world.” Semper Fidelis!

For more information on the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor, Marine Corps lore, and the history of Marine Corps insignia, see the following:

J. Duncan Campbell and Edgar M. Howell, American Military Insignia 1800-1851 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1963). Available as e-book from http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/38738?msg=welcome_stranger

Col. John A. Driscoll, USMCR, The Eagle, Globe, and Anchor 1868-1968 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1977)

Naval History & Heritage Command, “Navy Traditions and Customs: Nautical Terms and Phrases – Their Meaning and Origin” http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq101-2.htm Accessed on 7/23/2014

Maj. Edwin North McClellan, USMC, Uniforms of the American Marines: 1775 to 1829 (Washington, D.C.: Marine Corps History and Museums Division, 1982)

Tom McLeod, “Lineage of the USMC Eagle, Globe and Anchor,” Grunt.com http://www.grunt.com/corps/scuttlebutt/marine-corps-stories/lineage-of-the-usmc-eagle-globe-and-anchor/ Accessed on 7/23/2014

James G. Thompson, Decorations, Medals, Ribbons, Badges and Insignia of the United States Marine Corps: World War II to Present (Fountain Inn, SC: MOA Press, 1998)